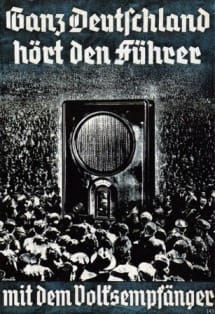

Nazi Germany’s Volksempfänger (people’s receiver) as propaganda channel

About this series

In the series History Rhymes, we zoom in on specific historical events that reflect themes more universally than isolated incidents. Our goal is to raise awareness of how similar patterns may be recurring in the present day.

Theme introduction

What happens when governments and tech giants align to control the flow of information? History offers chilling clues. From state radios to algorithmic feeds, the tools have changed - yet some patterns seem to re-emerge in new forms.

The theme of this episode

A Discovery in the Archives of a Media Museum

In the past, I had the opportunity to visit the archive of a national media museum. Among the many shelves filled with media equipment, a section was reserved for radios. In our world of digital media, this kind of nostalgia from bygone days - tube radios with their iconic tuning eyes - has something fascinating. In a collection like this, you can often guess the time period a radio comes from just by its design. My attention was drawn to a stunning piece with a vintage look and a distinctive Bakelite cabinet - it was clearly a model from the 1930s. Immersed in the nostalgia of old media equipment, I was unaware that this was no ordinary radio - or of the role it had played in history. The truth was deeply unsettling.

1933 - Volksempfänger VE301W, source Wikimedia

The Historical Context: From the Roaring Twenties to the Rise of Control

The 1920s, often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties (Goldene Zwanziger)," represented a period of post-war recovery and significant cultural transformation. This era was characterized by pronounced economic volatility, political instability, widening social inequality, and speculative financial activity - or ‘bubbles’. Concurrently, rapid technological innovation and industrial expansion facilitated the early diffusion of consumer goods such as automobiles (notably the Ford Model T), telephones, electric power in private homes, and radio broadcasting.

Triggered by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the Great Depression led to mass unemployment, widespread poverty, and social unrest across much of the world. In this climate of crisis, extremist political movements gained traction, most notably in Germany, where Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party rose to power in 1933. Historically, governments facing existential threats or severe instability tend to adopt more authoritarian measures to maintain control and prevent societal collapse. In such contexts, propaganda often emerges as a central tool for shaping public perception, reinforcing authority, and managing dissent.

Poster Radio Telefunken 1931, at that time a luxury item

Now let’s get back to radio. Before the 1930s, radio ownership in Germany remained relatively limited due to high costs and technological barriers. In the mid-1920s, a standard radio receiver cost between 250 and 400 Reichsmarks, equivalent to approximately two to four months’ wages for the average worker. This rendered radios largely inaccessible to working-class households, making them a luxury item primarily confined to the urban middle and upper classes. By 1930, only around three million radio licenses had been issued in a nation of over 60 million people, reflecting the slow pace of adoption. In addition to the high upfront cost of the devices, government-imposed license fees, the need for external antennas, and the uneven availability of electricity - particularly in rural areas - further limited widespread use. Thus, although radio technology had begun to take hold in the 1920s, its reach remained narrow, and its potential as a mass communication medium had yet to be fully realized.

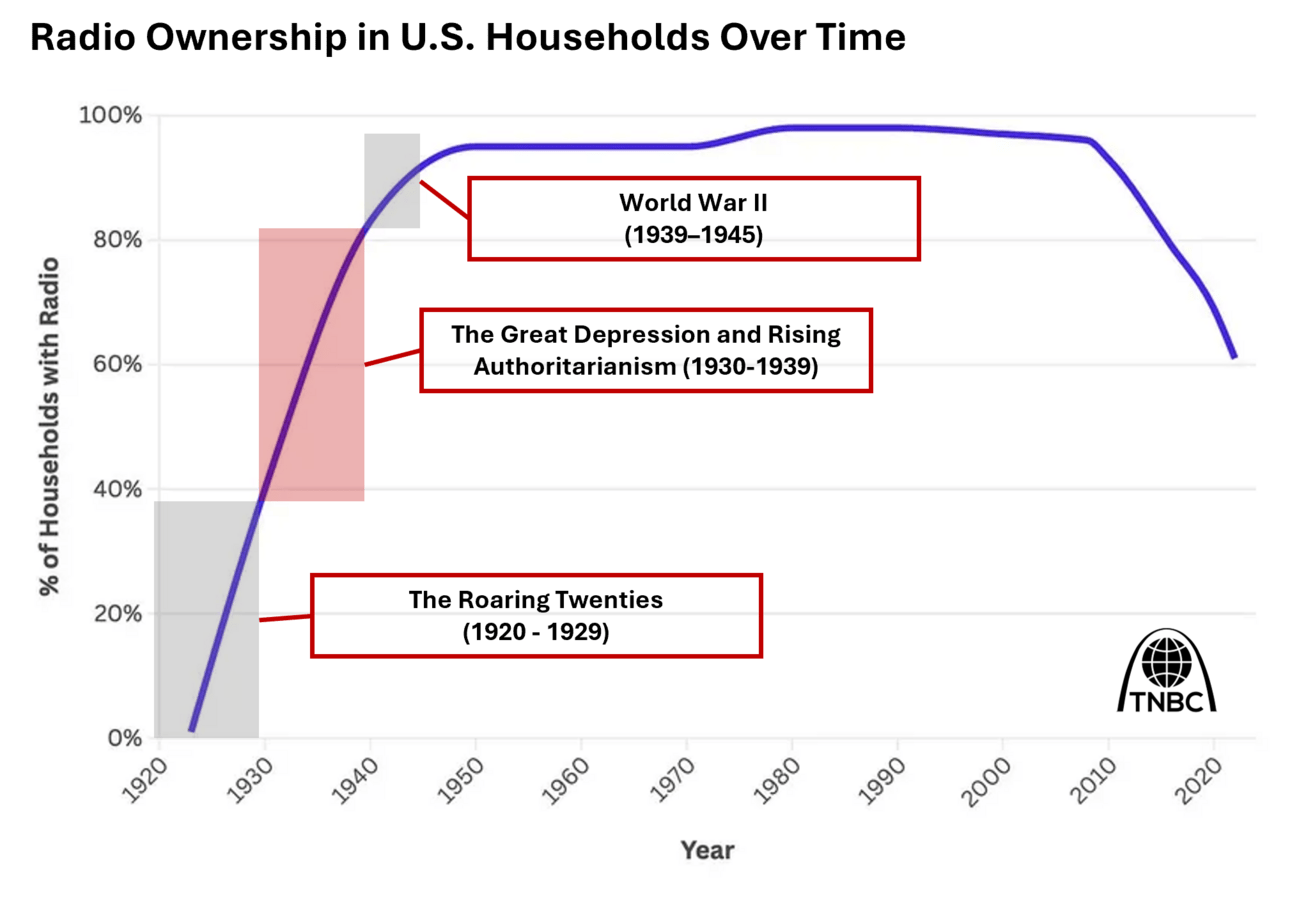

For reference, the figure below presents household radio ownership data from the United States - used here in lieu of comprehensive German statistics - and clearly illustrates the limited adoption in the early 1930s, a period characterized by high device costs and widespread economic hardship.

Thus, the convergence of rising authoritarianism and rapid technological innovation created the ideal conditions for the development of an exceptionally effective propaganda instrument.

Sources : U.S. Census, Edison Research, Consumer Technology Association, adapted for purpose

The Volksempfänger: Nazi Germany’s Use of New Media Technology for State Propaganda

The convergence of rising authoritarianism and rapid technological innovation created ideal conditions for the development of an exceptionally effective propaganda instrument. In Nazi Germany, this took the form of the Volksempfänger - or "people’s receiver" - a state-subsidized radio engineered to transmit centrally controlled messaging directly into the homes of millions. For a propaganda tool to be effective, wide distribution was essential: only through mass penetration could the regime saturate the population with its ideological narrative and ensure uniform exposure to state-approved content.

Affordability played a critical role in this strategy, and the omission of shortwave reception - while reducing production costs - served a more insidious purpose. By excluding shortwave frequencies, the Volksempfänger was intentionally designed to block access to foreign broadcasts, particularly from sources like the BBC or Radio Moscow, which could present alternative perspectives or contradict Nazi messaging. This limitation transformed the device into a tool not just of dissemination but of isolation - shielding listeners from competing worldviews. In recognition of its one-directional and manipulative nature, later models of the radio were mockingly referred to by critics as Goebbels-Schnauze (“Goebbels' snout”), highlighting the perception that it merely echoed the voice of Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda. The Volksempfänger thus stands as a striking example of how media technologies, when shaped by authoritarian intent, can be weaponized to control public discourse and suppress dissenting thought.

Industry in Service of Ideology: The Nazi Regime’s Alliance with the 'Big Tech' of the 1930s

The development and mass production of the Volksempfänger required close cooperation between the Nazi regime and leading German electronics firms, including Telefunken, Lorenz, and Siemens. Rather than nationalizing these companies, the state relied on a model of state-directed industrial cooperation, in which private manufacturers aligned with national goals in exchange for favorable contracts, state subsidies, and access to expanding domestic markets. The Volksempfänger was first introduced at the 1933 Berlin Radio Exhibition, under the directive of Joseph Goebbels.

The goal was to produce a receiver that was simple, affordable, and limited to German frequencies. Manufacturers supported this initiative not only due to the guaranteed scale of state procurement but also because aligning with the regime offered commercial security amid a recovering post-Depression economy. Ideologically, some executives and engineers shared nationalist sentiments, while others were compelled by political pressure and the tightening control of the economy under the Nazi Gleichschaltung policy. This partnership between the state and industry illustrates how authoritarian regimes can mobilize private sector innovation and infrastructure to serve ideological objectives, effectively transforming commercial technology into a vehicle for mass indoctrination.

Nazi propaganda poster from 1936. All of Germany is listening to The Führer with the Volksempfänger“ Source: Wikipedia

When Listening Became Treason: Radio as a Tool of Surveillance and Repression

The 1930s served as a prelude to World War II, and the outbreak of the war triggered even more drastic radio-related measures. At the beginning of the conflict, listening to foreign radio broadcasts became a criminal offense - labeled Rundfunkverbrechen (“radio crimes”). Radios now came with a clear warning at the tuning dial: “He who listens to the enemy will be punished with imprisonment; he who spreads intercepted messages will be executed.” This was far from an empty threat. According to a 1941 situation report, between 200 and 440 individuals were arrested each month for “enemy listening.” Between 1939 and 1942, Nazi statistics record a total of 2,704 convictions for radio-related crimes. These measures reflect how the regime transformed a household technology into an instrument of control - criminalizing not only access to information, but also the act of listening itself.

The First Tech-Driven Dictatorship: A Warning from Within

Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect and Minister for Armaments, reflected at the Nuremberg trials that Hitler's dictatorship differed in one fundamental point from all its predecessors in history. His was the first dictatorship in the present period of modern technical development, a dictatorship which made the complete use of all technical means for domination of its own country. Through technical devices like the radio and loudspeaker, 80 million people were deprived of independent thought. It was thereby possible to subject them to the will of one man.

So Does History Rhyme?

It is not the aim of this article to draw a direct comparison between the 1930s and the present day. Yet certain patterns are difficult to ignore. Understanding these parallels is not about drawing direct analogies, but about recognizing the conditions under which propaganda thrives, power consolidates, and societies become vulnerable to authoritarian influence.

Today’s world, like that of the interwar period, is shaped by the disruptive force of new technologies - now not radio, but AI-powered social media - emerging amid widening economic inequality, deepening political polarization, and resurgent nationalism. Both eras reflect a broader sense of societal fragmentation and disorientation, where traditional institutions struggle to maintain authority and trust.

Can today’s media evolve into and refined AI driven form of the Volksempfänger?

In the 1930s, the scars of World War I were still raw, and the global economy was reeling from the Great Depression. These pressures fueled mass unemployment, social unrest, and the rise of extremist ideologies promising order through strength. A similar unease can be felt today: geopolitical tensions are escalating, economic uncertainty persists, and democratic norms are under strain in many parts of the world. In both periods, fervent nationalism and identity-driven politics gained traction as populations sought clarity and control in times of profound disruption. The emotional climate - the mix of fear, anger, and longing for stability - bears some resemblance.

As governments and tech industries forge new relationships around information control and influence, the structural similarities with earlier eras raise urgent questions. How is media being weaponized today? What role does the tech industry play in shaping political narratives? And what lessons can we draw from the past to guard against the misuse of powerful tools in the present?

Beyond Dictatorships: The Subtle Machinery of Influence in Modern Democracies

The extreme authoritarianism of Nazi Germany in the 1930s was accompanied by an aggressive and highly centralized system of propaganda and censorship. This historical example has strongly shaped the modern connotation of the word propaganda, often limiting its association to overtly dictatorial regimes and totalitarian control over media narratives. However, this narrow framing can itself be misleading - and, arguably, a form of propaganda in its own right - for two important reasons.

A balancing act for governments “Freedom of Information” vs. “Propaganda”

First, propaganda is not exclusive to authoritarian systems. It is a technique of persuasion and influence that can be found across the political spectrum and in all types of governance. In democratic societies, propaganda often operates through more subtle mechanisms: selective framing, emotional appeals, repetition, and the alignment of corporate and political messaging. Rather than silencing dissent outright, it may drown it in noise, redirect attention, or emotionally manipulate through curated narratives.

Second, the Nazi regime's brute-force control of broadcasting systems - so overt it earned radios the nickname Goebbels' Schnauze (“Goebbels' snout”) - represents an obvious and easily recognizable form of propaganda. However, in today’s context, propaganda operates within a far more advanced and subtle technological environment, driven by AI-powered social media platforms rather than radio. But unlike the heavy-handed methods of the past, contemporary influence campaigns are often so refined and personalized that the average citizen remains unaware they are being manipulated at all.

This subtle manipulation is not incidental; it has become a core feature - indeed, the business model - of some social media companies. Personal data is used to algorithmically shape the content individuals see, reinforcing beliefs, emotions, and biases in ways that serve both commercial and political objectives. And just as in the 1930s, we again witness the convergence of government interests and corporate power. States collaborate with tech platforms - whether explicitly or through regulation, funding, or influence - creating an ecosystem where mutual benefit can be drawn from shaping public perception at scale.

Meta data centre, Source Meta media gallery

Controlling the Narrative: Today’s Tools in Action

What once seemed exclusive to authoritarian regimes slowly surfaced in the West - governments and tech companies aligning to guide what populations could see, share, and believe. Historically, crises such as political polarization, natural disasters, or armed conflict have served as catalysts for governments to expand mechanisms of social control. The Russia–Ukraine war exemplifies how modern states now leverage partnerships with technology firms to shape information flows and maintain public order.

Example 1: European Sanctions on Russian State Media

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the European Union took unprecedented steps to curb the spread of Kremlin-backed mediachannels within its borders. Among the earliest measures was the banning of Russian state-sponsored media outlets such as RT (formerly Russia Today) and Sputnik across all EU member states. The sanctions included not only the removal of these channels from broadcast and satellite networks but also the de-indexing and delisting of their content on major social media and search platforms, including YouTube, Facebook, Twitter (now X), and Google. While critics raised concerns about press freedom, the EU maintained that the move was necessary to protect public discourse and national security during wartime. This serves as yet another example of how governments seek to maintain control over the dominant narrative by restricting access to foreign media sources.

Example 2: Zuckerberg's Admissions: US Government Pressure and Social Media Manipulation

Mark Zuckerberg has publicly acknowledged in a letter to the House Judiciary Committee that the Biden administration exerted significant pressure on Meta to censor content, including during the COVID-19 pandemic and in relation to the Hunter Biden laptop story ahead of the 2020 election. He admitted that senior officials, including those from the White House, "repeatedly pressured our teams for months to censor certain COVID-19 content, including humor and satire," a decision he later deemed "wrong" and expressed regret for not being more outspoken about. Regarding the Hunter Biden laptop story, Zuckerberg confessed that Meta demoted the New York Post's reporting after an FBI warning about potential Russian disinformation, only to later recognize this as a mistake once the story's authenticity was clarified, noting, "in retrospect, we shouldn’t have demoted the story." This revelation suggests a pattern of government influence on social media content moderation, raising concerns about election interference and the suppression of information, though Zuckerberg emphasized that Meta made the final calls and has since adjusted its policies to resist such pressure moving forward.

Example 3: When the State Tweets: US Government Intervention and the Twitter Files Revelations

The "Twitter Files" - a series of internal documents released in late 2022 - unveiled the extent of U.S. government agencies' involvement in content moderation on Twitter. These files revealed that agencies such as the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security routinely communicated with Twitter to flag content related to topics like COVID-19, election integrity, and the origins of the virus. Twitter collaborated with federal agencies, notably the FBI, to suppress content, including the New York Post's Hunter Biden laptop story in 2020, which was flagged as potential disinformation despite lacking clear policy violations. The files also expose shadow banning of conservative voices, such as Stanford professor Jay Bhattacharya, and pressure from the Biden administration to censor COVID-19-related content, including satire. Notably, journalist Matt Taibbi highlighted how the State Department's Global Engagement Center (GEC), initially established to counter foreign disinformation, expanded its focus to include domestic content, raising concerns about free speech and government overreach. Taibbi criticized this shift, referring to it as "digital McCarthyism" during a congressional hearing.

Example 4: The EU’s Information Policy: Safeguards, Power, and the Risk of Overreach

The European Democracy Shield (announced 2024–2025) aims to counter foreign information manipulation, preserve election integrity, and support independent media—but critics warn it may give the state new powers over digital narratives. European Parliament+1

The Digital Services Act (DSA) mandates that very large platforms address “systemic risks” like disinformation, requiring transparency, audits, and content moderation obligations. Wikipedia+2CSIS+2

The EU “Chat Control” / CSAM Regulation (a proposed law) would require scanning of private messages (including encrypted ones) for child sexual abuse material—raising fears of sweeping backdoors into private communication. Wikipedia+1

Under the DSA’s Disinformation Code now embedded into law, platforms must audit and mitigate disinformation risks—some see this as a lever for de facto censorship. Tech Policy Press+1

Proposals around scanning chat messages, decrypting digital communication, or linking central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) to surveillance capacity are being discussed in European policy circles as part of broader digital security agendas.

The push for centralized media resilience, fact-checker networks, and government-platform “coordination” units (e.g. via the Democracy Shield’s media resilience components) may evolve into more coercive tools of narrative control. ai4debunk.eu

Example 5: Government-Tech Collusion in Platform Censorship

Another stark example of modern state - tech cooperation comes from the U.S., where Google LLC (parent company of YouTube) recently admitted that during the Joe Biden administration the company faced “repeated and sustained” pressure from the government to censor content related to COVID-19, election integrity, and other politically sensitive topics. House Judiciary Committee+1 In a September 23, 2025 letter to the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, Google pledged to reinstate accounts previously removed from YouTube, explicitly acknowledging White House influence. yahoo.com+1 This case highlights how, even in a democratic context, the alliance between big government and big tech can morph into a powerful mechanism for narrative control and suppression of dissent.

History’s Echo: What to Remember, What to Watch

History shows that when governments and information technologies converge, control follows. In the 1930s, the Volksempfänger gave political power a direct line into the homes and minds of citizens. Today, the partnership between Big Tech and Big Government has created a far more sophisticated version of the same mechanism. Whether under the banner of “safety,” “public health,” or “democracy protection,” the ability to shape what billions see and hear now rests in the hands of a few companies - often acting at the urging of the state. The technology has changed - but the temptation to steer public thought has not.

Crises Amplify Government Influence Over Media In times of war, unrest, or emergency, democratic governments - like authoritarian regimes - often seek greater control over information to maintain order and legitimacy.

Big Tech Is Susceptible to State Pressure. Corporations that control communication infrastructure, especially social media, are vulnerable to subtle and overt pressure from governments to moderate, censor, or amplify content in ways that serve political agendas.

Media Control Is Not Exclusive to Dictatorships. The use of media for social control and propaganda is not limited to authoritarian regimes. Democracies, too, have employed such tactics - sometimes in the name of national security, public health, or social cohesion.

Digital Technology Enables Invisible Influence. Modern propaganda doesn’t always look like old-school censorship. Algorithms, shadow banning, content prioritization, and platform policies enable sophisticated forms of influence that are harder to detect - and easier to normalize.