From the Opium Wars to the Petrodollar to the Fentanyl Crisis: A Geoeconomic Inquiry into the Recurring Logics of Imperial Trade, Monetary Power, and Addictive Commodities

About this series

In the series History Rhymes, we zoom in on specific historical events that reflect themes more universally than isolated incidents. Our goal is to raise awareness of how similar patterns may be recurring in the present day.

Theme introduction

Trade imbalances, currency power, addictive commodities, and hegemonic ambition - these forces have shaped empires and sparked conflict for centuries. Today, they return in new forms, but with familiar consequences.

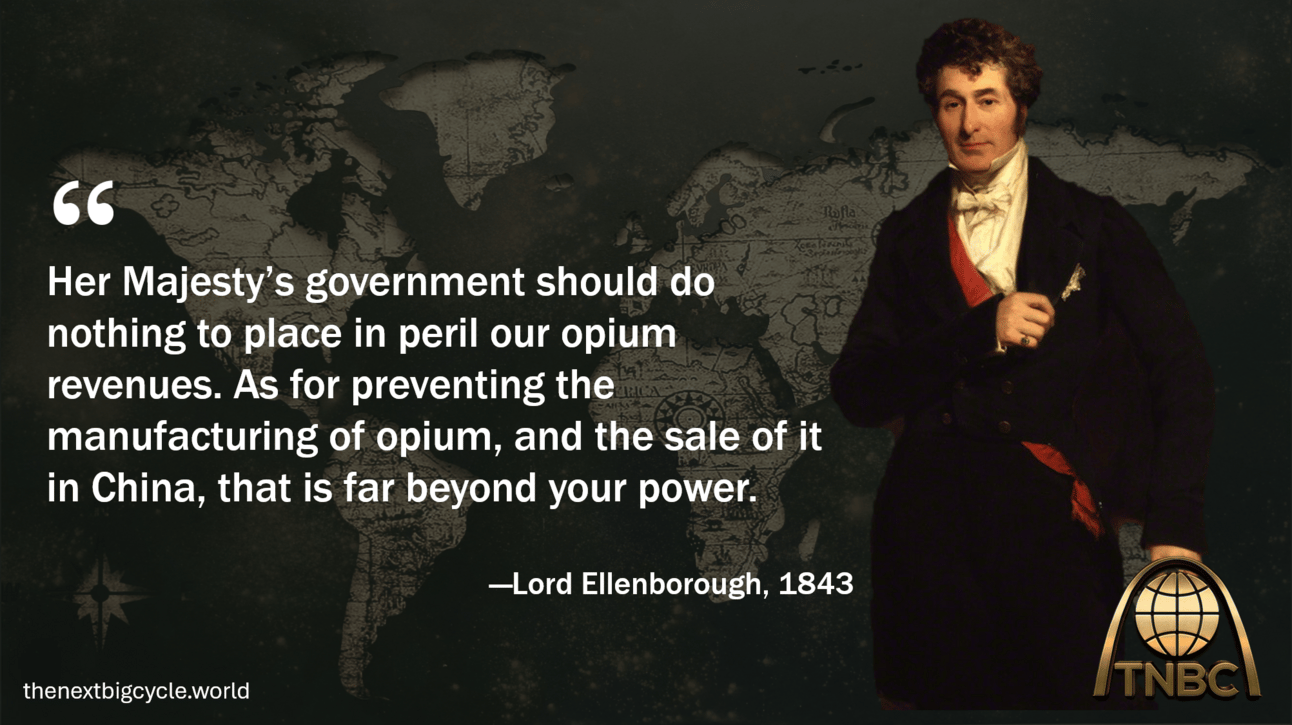

Her Majesty’s government should do nothing to place in peril our opium revenues. As for preventing the manufacturing of opium, and the sale of it in China, that is far beyond your power. —Lord Ellenborough, 1843

The Most Fascinating Story of Shifting World Orders and a Dark Chapter in History

As I delved into the story of the Opium Wars, I became captivated by how vividly it reflects so many themes that continue to shape our world today. The clash between East and West, the relentless cycles of rising and falling powers, ruthless mercantilism, fierce naval battles, and the colonial exploitation of India - all intertwined with the desperate lengths an empire will go to maintain its dominance.

What struck me most was how closely these historic events mirror the geopolitical and economic struggles we face now. I believe you may find this story just as fascinating and revealing as I did - offering fresh insight into the recurring patterns of power, greed, and resistance that still define our global stage. It powerfully illustrates what the next great historical cycle is about - and how the key themes of the past continue to shape the present.

It is not surprising that countless books have been written on this subject

Clash of Empires: China and Britain on the Eve of the Opium Wars

In the early 19th century, the world was in the grip of shifting hegemonies. China, under the Qing Dynasty, saw itself as the central power in a centuries-old tribute-based system, economically self-sufficient and culturally superior, with limited interest in foreign goods. Great Britain, by contrast, was emerging as the dominant global empire, fueled by industrialization, maritime power, and a hunger for new markets and resources.

The British demand for Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain created a growing trade imbalance, as China demanded payment in silver and offered little in return. Britain, eager to correct this imbalance and assert its commercial power, pushed for greater access to Chinese markets - challenging China's restrictive trade system centered in Canton.

These tensions unfolded at a time when the British Empire was expanding its global influence, and China, though still vast and powerful, was increasingly vulnerable to external pressure. The stage was set for a clash not just of economic interests, but of worldviews - between a rising industrial empire and an ancient imperial power resisting integration into a rapidly globalizing economy.

Early 19th century Chinese porcelain part tea service

The Roots of Imbalance: Silver, Tea, and the Uneven Trade Between Britain and China

China had little interest in British manufactured goods, believing its own economy to be self-sufficient and superior. As a result, Britain was forced to pay for Chinese exports in silver, the only currency the Qing government accepted for international trade. This insistence on silver was rooted in China’s traditional view of monetary stability and its desire to avoid foreign economic influence, as well as its mercantilist policy of accumulating precious metals.

This one-sided flow of silver created a significant trade imbalance for Britain. While the empire generally maintained more balanced or even favorable trade relations with other parts of the world - exporting textiles, machinery, and colonial goods - its trade with China became a financial drain. Over time, the deficit became politically and economically untenable, sparking anxiety in London over bullion outflows and the sustainability of empire-wide commerce. The urgent need to reverse this imbalance and secure access to Chinese markets on more favorable terms became a central driver behind Britain’s increasingly aggressive trade policy toward China - setting the stage for confrontation.

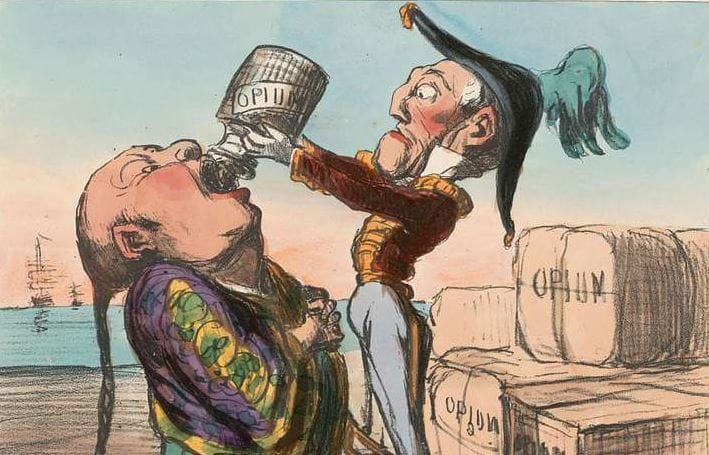

Turning the Tide: Britain's Opium Strategy and Its Devastating Impact on China

Faced with an unsustainable trade deficit and the steady outflow of silver to China, Britain turned to a darker solution: opium. Produced in large quantities in British-controlled India, opium offered a highly profitable commodity with a growing underground demand in China. Although opium was officially banned by the Qing government due to its addictive and socially corrosive effects, British merchants - operating through intermediaries and protected by imperial policy - began smuggling vast quantities of the drug into Chinese ports, particularly through Canton (Guangzhou). Over time, this reversed the silver flow; now, silver was leaving China to pay for opium, destabilizing the Qing economy and draining its treasury.

The social consequences were equally devastating. Opium addiction spread rapidly across all levels of Chinese society, weakening the workforce, undermining public health, and fueling widespread corruption. Officials, soldiers, merchants, and even scholars fell prey to the drug. As addiction surged, so did political tension: Chinese authorities, alarmed by both the moral decay and the economic hemorrhaging, began cracking down on the trade. Britain's calculated use of opium not only redressed its trade imbalance but also created the conditions for a profound geopolitical rupture—one that would explode into open war.

Chinese opium smokers Source: Wikimedia

Gunboats, Treaties, and the Fall of an Old Order: How the Opium Wars Signaled a Hegemonic Shift

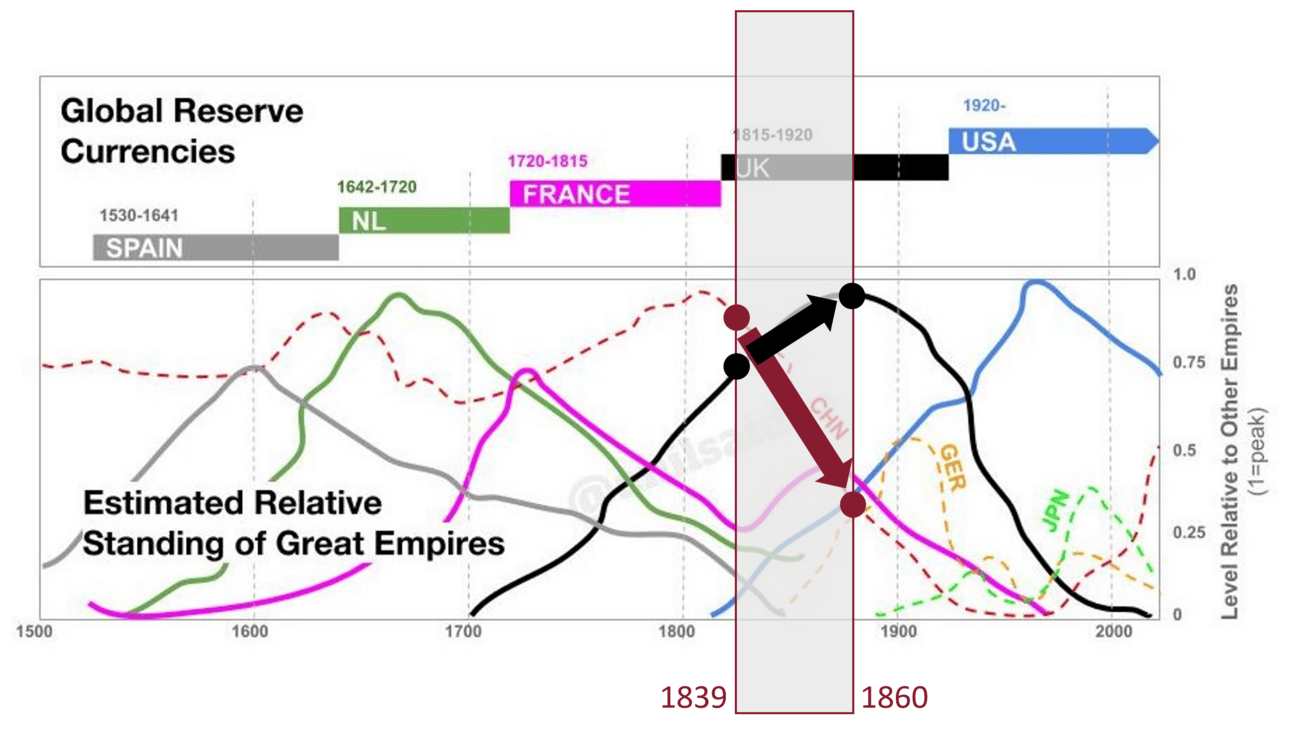

The crisis came to a head in 1839 when Chinese official Lin Zexu, acting with rare moral clarity and imperial authority, seized and destroyed thousands of chests of British opium in Canton. In response, Britain deployed its navy, launching the First Opium War (1839–1842). The Qing Empire, still grounded in pre-industrial military structures and diplomatic norms, found itself utterly unprepared for Britain’s steam-powered gunboats and global naval reach. China’s defeat led to the Treaty of Nanjing, which forced it to cede Hong Kong, open key ports to foreign trade, and pay heavy reparations - all without reciprocal obligations from Britain. It was the first in a series of “unequal treaties” that shattered China's sovereignty and set a precedent for Western powers to carve out spheres of influence through coercion and war.

The Second Opium War (1856–1860) reinforced this new global order. Britain, now allied with France, extracted even more concessions - legalizing the opium trade, expanding foreign access to China’s interior, and establishing permanent diplomatic presence in Beijing. These wars were more than just imperial skirmishes over trade. They were a signal that the old Sinocentric world order, which had defined East Asia for centuries, was being replaced by a new global hierarchy dominated by Western industrial powers.

Relative standing Great Brittain and China during timeframe of opium wars. Source: Ray Dalio, Principles for dealing with the changing world order, 2021 adapted for purpose

Britain’s victory marked the consolidation of its status as the preeminent global hegemon - a power that could use not only trade but force to impose its will across continents. For China, it was the beginning of a long decline, and for the world, it was the stark unveiling of a modern era defined by naval supremacy, economic coercion, and globalized imperialism. The Opium Wars thus did not simply end a regional dispute - they ushered in a fundamental reordering of global power, where military-industrial strength, not cultural centrality, would dictate a nation’s place in the world.

The East India Company iron steam ship destroying the Chinese war junks in Anson's Bay, on 7 January 1841. Source: wikimedia

Lessons from a Lost Balance: What the Opium Wars Teach Us

The Opium Wars reveal how trade imbalances, monetary policy, and economic desperation can drive even the most "civilized" nations to morally indefensible actions. Britain’s willingness to exploit addiction and wage war to correct its silver drain exposes how far a declining or overstretched empire may go to preserve global dominance. At the same time, China’s refusal to adapt its trade system and recognize shifting power dynamics left it vulnerable to exploitation.

This clash between a rising industrial power and an old-world empire illustrates a recurring pattern in history: when economic tensions meet technological asymmetry and ideological rigidity, conflict often follows. As we turn to today’s world, the echoes are unmistakable - currency struggles, resource dependency, asymmetric trade, and the use of soft and hard power to shape global order. The mechanics may differ, but the underlying forces remain strikingly familiar.

So Does History Rhyme?

This article offers only a brief overview of how history appears to rhyme across centuries. It is not intended as a comprehensive or in-depth analysis of either the Opium Wars or the complex dynamics between the United States and China today. Rather, it serves to highlight recurring patterns - trade imbalances, addictive commodities, shifting hegemonies - that continue to shape global affairs. The goal is not to equate past and present directly, but to provoke reflection on how the underlying forces of power, economics, and ambition often play out in strikingly familiar ways.

Echoes in the Present: U.S.–China Tensions and the New Opium Wars

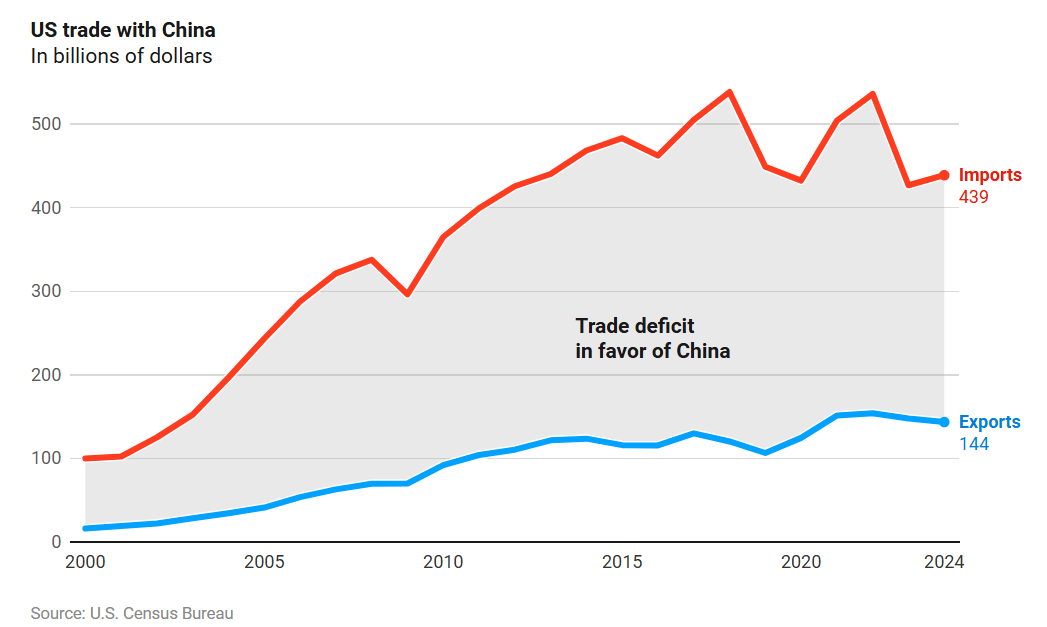

Today’s geopolitical landscape bears uncanny similarities to the dynamics that led to the Opium Wars nearly two centuries ago. The United States, like Britain then, is a dominant but increasingly overextended power facing a rising challenger in China. One of the most glaring parallels is the massive U.S. trade deficit with China. For decades, the U.S. has imported vast quantities of Chinese goods - electronics, clothing, machinery - while exporting comparatively little. This imbalance has sparked political backlash, tariff wars, and growing concern over the long-term erosion of America’s industrial and economic base. As in the 19th century, trade is not just about goods, but about power, leverage, and prestige.

Example #1: Trade Imbalance and Economic Tensions

In the 19th century, Britain’s massive trade deficit with China, driven by demand for tea and luxury goods, led to economic strain and political urgency. Today, the United States finds itself in a similar position with China - importing far more than it exports, creating a structural imbalance that has fueled protectionist sentiment, political division, and a deep questioning of economic dependency.

US trade with China - Source: U.S. Census Bureau

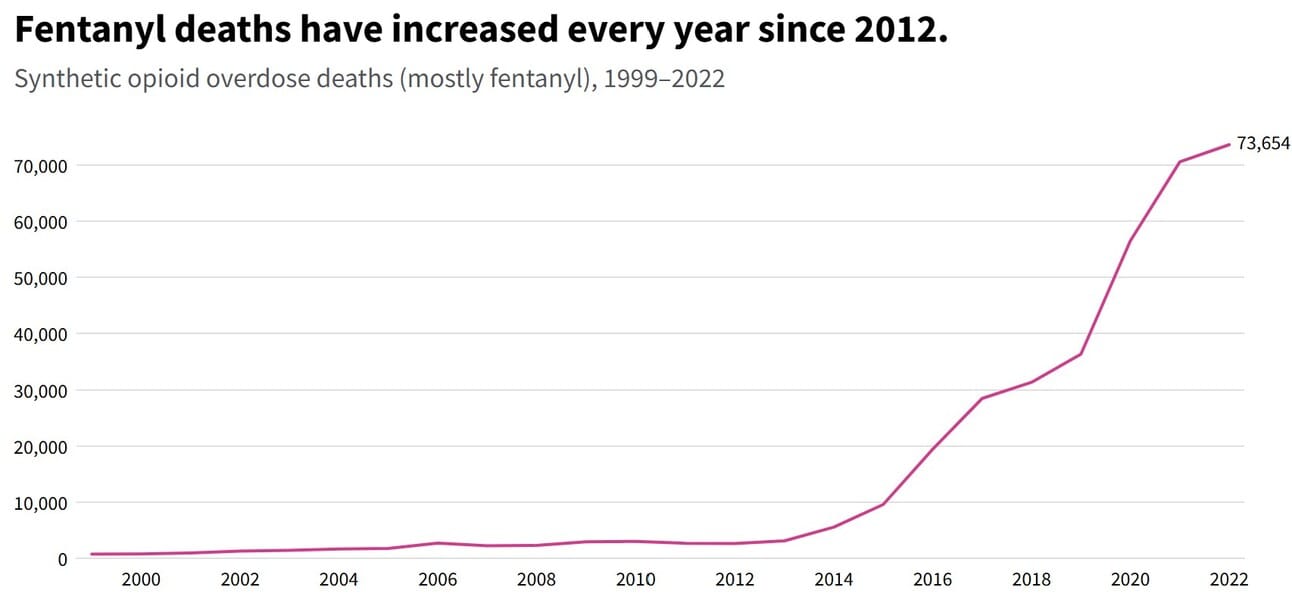

Example #2: Narcotics and National Erosion

The opium trade once hollowed out Qing China from within, both socially and economically. Now, the U.S. faces its own internal crisis in the form of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid largely sourced from or routed through China. Like opium then, it flows illicitly, creates addiction on a massive scale, and leaves the receiving nation politically and morally outraged - yet struggling to stop it.

Source: Centers for Disease Control

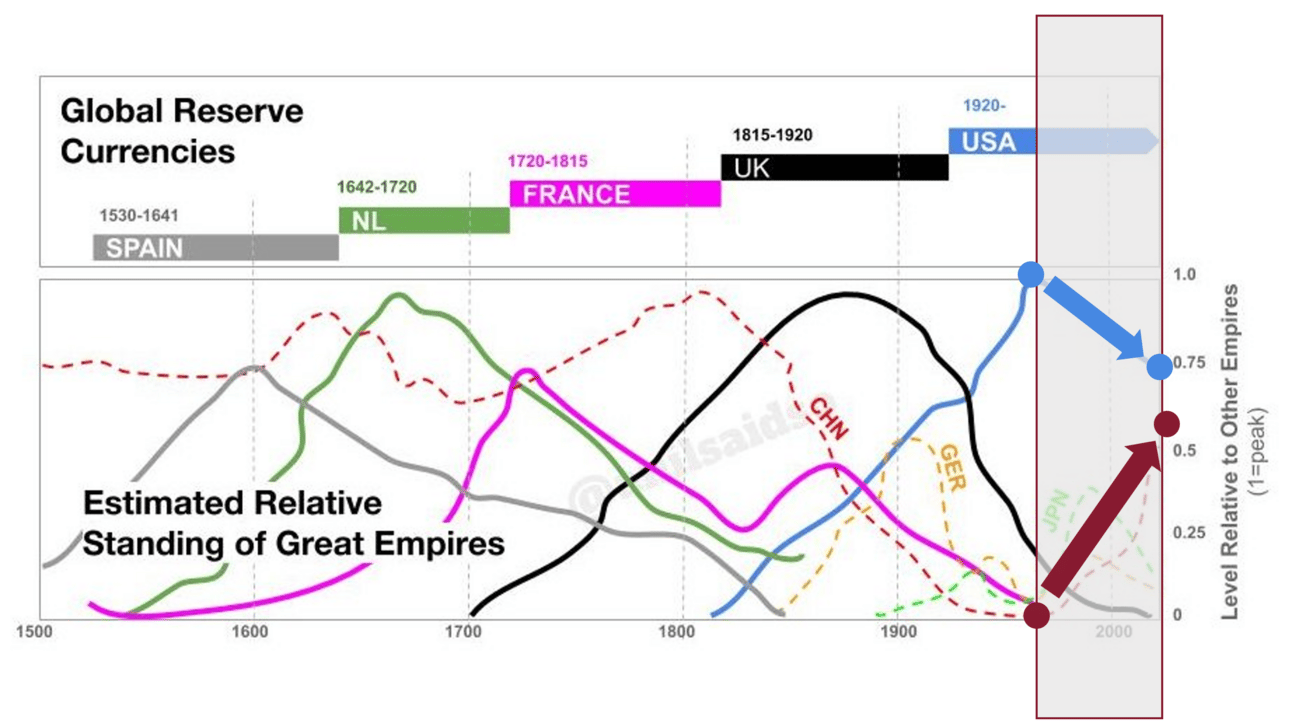

Example #3: Rising Powers, Declining Confidence

Britain’s use of opium was part of a broader effort to retain global supremacy as its trade and influence came under pressure. Today, the U.S. is showing classic signs of hegemonic strain: growing debt, institutional dysfunction, and global pushback. Meanwhile, China is asserting itself as a rising power through technological development, military expansion, and diplomatic ambition - reshaping the balance of power.

Relative standing United States and China today. Source: Ray Dalio, Principles for dealing with the changing world order, 2021 adapted for purpose

Example #4: Tension, Conflict, and the Path Ahead

The Opium Wars were not inevitable - but they were the result of unresolved tensions between a declining hegemon and a resistant empire. Similarly, tensions over Taiwan, maritime control, and financial systems are building today between the U.S. and China. While full-scale conflict is not certain, the historical pattern warns us: when trade, power, and pride collide, diplomacy is fragile - and the consequences can redefine the world order.

History’s Echo: What to Remember, What to Watch

The Opium Wars were not just about trade or territory - they were about power, pride, and the desperate moves empires make when their dominance is threatened. Today, similar forces are once again in motion. While history never repeats itself exactly, the echoes are loud enough to warrant attention. Trade imbalances, addiction crises, rising rivalries, and shifting global rules are not relics of the past - they are signals of where we may be headed. What matters now is whether we recognize the patterns in time to avoid repeating their most destructive outcomes.